What topics and concepts does a course cover?

Mapping for Curricular and Assessment Efficacy

White paper written by Dr. Divya Bheda in partnership with eLumen

Five strategies for improved curriculum maps that further institutional effectiveness and continuous improvement.

This white paper continues the discussion from our webinar with Dr. Divya Bheda, titled Building the Right Foundation, the Right Way: Curricular Mapping for Equity and Student Success. Watch the webinar recording here.

Executive summary

Curriculum mapping is a pivotal tool with extensive potential to inform and enhance educational excellence. This paper introduces five strategies for engaging curriculum mapping on campus, emphasizing the importance of utilizing assessment performance data to drive institutional improvement and enhance student learning.

By implementing and learning these strategies, educators and institutions can foster data-guided decision-making to improve student success.

Background

What is curriculum mapping?

A curriculum can be described as a complex combination of content, learning materials, teaching strategies, assessments, and the educational environment (Harden, 2001). Curriculum mapping provides a two-dimensional representation of this combination, facilitating an effective curriculum development process.

Curriculum mapping is a widely recognized best practice in K-12 education that has built upon the work of esteemed scholars like Dr. Heidi Hayes Jacobs (1997, 2004, 2010) and Janet A. Hale (2007). Numerous books, studies, and articles have shown the value and benefits of the curriculum mapping exercise. A great deal of others offer guidance on how maps can be built (horizontally or vertically), maintained, and used.

In higher education, maps are often used to meet accreditation requirements (regional and professional) to demonstrate curricular coverage and assessment checkpoints. Curriculum maps can address questions like:

What should students be able to do after completing a course?

What learning outcomes does a course or program assess?

How do learning outcomes in the program connect with each other?

The importance of faculty engagement

At its core, the curriculum mapping method is meant to be used for ongoing curriculum review and development: faculty must periodically collaborate to review, align, and update curriculum maps. Therefore, it is crucial to engage faculty members in this exercise on a regular basis.

While educators are generally supportive and willing to participate in the mapping process (Joyner, 2016), a question remains:

How frequently does this collaboration actually take place?

Candid interviews and informal surveys conducted by the author (during higher education conferences and professional development events) yield diverse responses from educators: some state that their institutions rarely or never perform these periodic reviews, while others maintain that they visit their curriculum maps regularly.

Given this wide range of responses, it could be inferred that the perceived value of curriculum mapping is limited to addressing the requirements of accrediting bodies. In reality, the curriculum mapping exercise has the potential to advance institutional efficiency, engage and develop faculty members, and improve student success. A robust curricular map enables curricular review and analysis that helps educators eliminate gaps and redundancies, correct misalignments, and explore scaffolding opportunities to connect and coherently build various curriculum components across time of study (edglossary.org, 2013).

Five strategies for improvement

This white paper offers five lessons learned based on over a decade of experience leading and facilitating curricular initiatives and mapping exercises across various institutions and programs. The application of these strategies harbors the potential to enhance curricula and mapping procedures across diverse institutions and programs. They also contribute to advancing educational efficacy and fostering continuous improvement (CI) for educators universally.

Introduced by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe in Understanding by Design (1998), Backward Design (BD) is an approach to curricular planning and development that is widely used in the K-12 world. The BD framework asks instructors to follow three steps:

Step 1

Identify the desired learning outcomes. Instructors should consider the learning goals that will help establish curricular priorities.

Step 2

Determine evidence that will demonstrate student attainment of the desired outcomes. Plan and design the assessments (or assignments) that students will complete.

Step 3

Plan the learning activities and instructional strategies that align with the desired outcomes. This step ensures that the taught content is relevant for students.

Once the steps have been completed in this order, educators will have laid out a scaffolded, aligned curricular plan. This relevant, aligned content is crafted to clearly advance student performance and demonstrate achievement of the outcomes.

For many post-secondary instructors, this approach may feel counterintuitive and unfamiliar given the existing, ubiquitous practice of deciding the content first and the outcomes last. With a traditional approach, educators focus on seminal works, scholars, or knowledge areas in the field that they believe students must master and then decide and finalize the assessments (and, at times, even the learning outcomes). However, this traditional curricular approach is antithetical to student-centered teaching and learning logic (Hitchcock, et al., 2002; Jankowski & Marshall, 2017). This course content may be out of touch with what is needed for student learning in the current context (Prideaux, 2003). Thus, using the BD approach, assessments are plugged in at the end of the process to measure student mastery.

The Backward Design approach helps educators move towards more competency-based learning, because the focus is on identifying the students’ destination, the learning goals and outcomes, and then using the determined assessments to clarify if they have been achieved by the students.

Well-designed assessments play a crucial role in helping educators validate student attainment of determined outcomes. Educators should concentrate their efforts on the impact of the curriculum rather than their intentions for the curriculum. To support a backward design approach, consider a few guiding questions:

- What should the learner be able to do or demonstrate?

- How will educators know that the learner has mastered the necessary knowledge and skills that their discipline requires?

By thoughtfully answering these questions, you are developing robust curriculum maps and aligning learning goals.

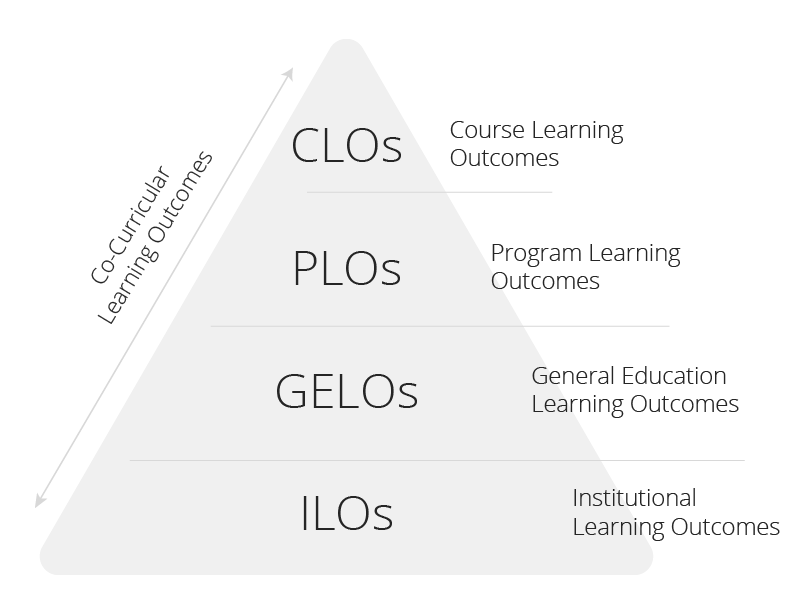

The outcomes documented in a map might include institutional learning outcomes (ILOs), program learning outcomes (PLOs), general education learning outcomes (GELOs), course learning outcomes (CLOs), and co-curricular learning outcomes.

Types of outcomes in a curriculum map

There are currently at least three different maps often used in higher education to support institutional alignment: outcomes hierarchy maps, academic program maps, and assessment maps.

Outcomes hierarchy map

The outcome mapping strategy of an institution includes alignment of each outcome map at the individual discipline level to the overarching institutional plan. For the purposes of this paper, we will call this the outcomes hierarchy map.

The outcomes hierarchy map tries to connect different levels and types of outcomes with each other. Some examples include connecting PLOs to ILOs, GELOs to CLOs, or discipline competencies to CLOs, among others.

This type of relationship mapping is often done to establish connections between outcomes within the institution. This mapping process allows institutions to identify and address curricular gaps, redundancies, and misalignments as it ties to the larger institutional context and student learning journey. It also facilitates drawing inferences about the achievement of student learning outcomes at the institutional level that are linked to the ones that are assessed at the course or program level.

What it does

Identifies student learning outcomes and curricular connections within and across the institution.

How it's used

To establish connections between different levels of outcomes.

Benefits

Examines coherence of students' educational experience in line with institutional mission, goals, and outcomes

Helps to identify and address gaps, redundancies, and misalignments

Challenges

Requires institution-wide leadership to collaborate and be open to change

Can be difficult to assign ownership of mapping process and where it must live

Academic program map

The second type of map used is the academic program curriculum map. It focuses on the student journey within an academic program, or pathway, and states curricular intent. This map reflects what educators are planning to teach and where or when they plan to teach it in the educational journey.

Program curricular maps rely on content and instructional coverage to determine the stage of learning a student will be in. Concepts and competencies can be introduced, developed, and reinforced. Consequently, students can be expected to be proficient in those competencies or concepts at different stages in the program. This attainment is then laid out in the map.

These maps use some version of the introductory, developed, reinforced, and proficient (IDRP) approach and structure. These maps are usually submitted to accreditors for program approval and curricular quality documentation. They are sometimes used to review or confirm scaffolding of learning and alignment. However, they frequently continue to be developed and maintained by only one member of the educational team – often a program director or senior faculty member of the program.

What it does

States curricular intent, content descriptions, or competency attainment and distribution along program pathways.

How it's used

To reflect what, where, and when a concept is being taught within a student’s educational journey.

Benefits

Can be submitted to accreditors for program approval

Helps document curricular scaffolding and coverage

Clarifies learning intentions

Challenges

Does not rely on the Backward Design approach

Often considered a one-and-done compliance process at the beginning of program creation

Ongoing maintenance is usually for accreditation so can be minimized

Assessment map

The third type of map is the assessment map, which narrows the focus to mapping the construction of the assessments and solidifies the placement or source of the needed student performance assessment data.

These are less frequently built and maintained in higher education, but are arguably one of the most actionable and data-generating maps. Because it explicitly ties this student assessment performance data to outcomes very specifically, this map outlines the specific assessments in the order of students having to take them and aligns those assessments to the CLOs, PLOs, GELOs, and ILOs respectively, separately. Linking assessments and assignments specifically and separately to each type of outcome level allows educators to be able to make valid inferences about student learning on any PLO, ILO or CLO directly rather than making inferences about student achievement of a PLO because of its connection to a nested CLO. It helps avoid skip-level connection inferences about student learning that the outcomes hierarchy map enables. This type of direct data holds up to curricular audits and helps educators get true information and insights about student learning based on assessment performance.

Thus, assessment maps allow for robust curricular gap analyses that can be conducted when assessments don’t align with all the different levels of outcomes or when certain outcomes appear to be missing assessments. These maps detail relationships and hierarchies and allow for map alignment audits and comprehensive curricular mapping and scaffolding audits. They also enable the general, comprehensive gathering of valid and reliable student assessment data over time to assess performance trends and plan student, curricular, and instructional interventions and improvements as needed for student learning and success.

What it does

Links student assessment performance data to specific assignments to reflect learning and curricular impact.

How it's used

To assess student performance trends, curricular quality, and curricular impact to plan interventions and support learning.

Benefits

Provides student performance data, enabling initiatives for student success (e.g. student learning intervention planning and equity advancement)

Helps identify and address curricular gaps and redundancies

Allows for the auditing and improvement of other maps and scaffolding of learning

Challenges

High load/heavy lift activity initially

Requires time and ongoing effort

Requires significant faculty engagement and commitment

In higher education, various versions of all three types of maps are layered on top of each other and used for various purposes, including accreditation compliance, continuous program improvement, and student learning and success. However, it is important for educators to keep in mind the different purposes and uses of the three different maps, and build and use maps in discerning ways accordingly (Sumsion & Goodfellow, 2004). One map outlines curricular connections, the second map displays curricular intent, and the third map captures and reflects curricular impact. The use of these maps must factor those purposes in how they affect and/or limit the visualization and interrogation of the curriculum. Overall, all maps offer educators the power and possibility to audit connections, alignment, and scaffolding, as well as to make corrections as needed to better ensure learning intention matches learning impact. Using the right map for one’s needs assures better use and utility of the maps.

For any map to be actionable, the learning outcomes must focus on clearly defining and measuring the behaviors, habits, attitudes, abilities, skills, and knowledge areas (we will refer to these as will refer to these as BHAASKs) that students need to demonstrate proficiency in. When we talk about student learning and assessment, we often restrict assessment to measuring knowledge, skills, and, occasionally, traits. However, now more than ever, with artificial intelligence and access to unlimited information only a few clicks away, we need to delve into what we want students to learn, know, and do.

Thus, focusing on the habits, attitudes, behaviors, and abilities we want students to learn comes into play as added layers to knowledge and skills. When assessments are planned to capture only the knowledge and skills of learners, they can often be measured in meaningless, irrelevant contexts without real-world application or transferability. However, the added elements of behaviors, habits, attitudes, and abilities brings in the nuance necessary to ensure learning and assessments are real-world, relevant, and meaningful with direct transferability and applicability for the learner.

This operationalization of the learning outcomes by clarifying the specific BHAASKs that learners must be able to demonstrate, is key. Operationalizing the outcomes using BHAASks also means that the outcomes must be measurable and observable via assessments. Using Bloom's Taxonomy, educators can engage in a holistic and iterative BD approach and comprehensively outline all the BHAASKs learners should be able to do or demonstrate at the end of their educational journey (see IACET.org’s Primers on Learning Outcomes and Bloom's Taxonomy for an easy, consumable starting point and resource). In our maps and assessments, this articulation of specific, nuanced BHAASKs must now encompass how these BHAASKs would appear or be deployed in the real world – as envisioned by the educators. We should consider the professional field, the socio-political realities, the advances in technology, learning theories, and more. This endeavor constitutes the operationalization of the outcomes.

Operationalization of outcomes supports a more authentic and reliable assessment design. Specific and clear outcomes with well-aligned assessments strengthen the learning journey and signal the curriculum’s relevance, applicability, and quality to all. Once operationalized, the outcomes can be collated and sequenced for robust alignment within the map.

This recursive process of operationalizing outcomes and assessments with clearly defined boundaries and scope crystalizes the specifics of what is expected of the learner. This step is key to learner success. Robust operationalization of outcomes ensures valid nesting of outcomes where the right CLOs and BHAASKs are taught in the right courses and live within the right program and/or institutional learning outcomes. Strong operationalization also ensures true connectivity, powerful alignment, and intuitive scaffolding between outcomes in and across the curriculum for more authentic, structured, and meaningful student learning. Additionally, when the outcomes are well illuminated and operationalized, the corresponding stronger and more valid connected assessments offer more nuanced and accurate performance information resulting in data for action.

Well-operationalized outcomes connected to student assessments, and further down at the rubric level as criteria/metrics tracked within the assessments, enables educators to separate the modality of assessment from the BHAASKs more easily. Current assessment designs and student assessment performance data often conflate assessment modality proficiency with outcome proficiency making it difficult to draw valid and reliable inferences about student learning. For example, when an assessment or assignment is a long written paper (one modality) vs. an oral presentation (another modality), a student’s ability to engage in appropriate writing technique, style, and citations is conflated with their demonstration of their learning of the subject matter requested. Similarly, a strong or weak orator or strength or lack of competence with using powerpoint in a presentation assessment/assignment on patient safety and care for example in a Nursing course will impact the assessment performance. Thus, modality or student comfort in the assessment delivery medium intermingles with student competencies required of the profession or discipline. This conflation impedes learner assessment performance data quality, and in turn decision-making about any curricular examination and improvement based on that data. Parsing out modality from the BHAASKs is a necessary step.

Valid meaning making from the assessment data generated increases with greater distinction between how a student is assessed (modality) and what the student is being assessed on (outcomes or BHAASKs). Montenegro & Jankowski (2017) raise this as a student equity concern in assessment. Thus, the data becomes more actionable when robust operationalization and integration of outcomes occurs, and those outcomes are further powerfully connected with the student assessments and assessment elements such as rubrics while being able to distinguish it from modality proficiency. Clarifying BHAASKs and offering different modalities to showcase the discipline specific and appropriate way of demonstrating the BHAASK ensure applicability and real-world relevance of skills learned. It enables precise student interventions for powerful learning and success.

In higher education, curriculum mapping has often been relegated as a task for an individual. It has been seen as an exercise in document production, compliance, accountability reporting, and as a one-time or sporadic effort rather than as a recursive, iterative, and ongoing process for continuous improvement.

When thoughtfully designed and systematically examined through regular and collaborative review and analysis, maps become living documents.

Mapping success stories often entail faculty coming together to explore opportunities for curricular improvement and change to advance student learning and program and institutional success (Spencer et al., 2012; Uchiyama & Radin, 2009).

Faculty conversations are important, but we must consider all stakeholders when developing curriculum and maps. Administrative staff are vital in this conversation, as they can speak to the achievement of BHAASKs through the assessment co-curricular learning outcomes. Alumni, professional colleagues, and other external community members and stakeholders can offer real-world insight and advice on the competencies needed in and beyond the profession or discipline.

Learn more about assessing co-curricular outcomes in our webinar with Dr. Chiara Logli from Honolulu Community College.

All of these stakeholders can be brought together, for not just the creation of, but also the periodic reviews of maps. They can examine the assessment performance data and other contextual factors and inform curricular and mapping advancement. Having regular diverse and inclusive stakeholder community conversations is important because student learning involves the whole institution in the learner’s educational endeavor (Plaza, et al., 2007; Winkelmes, 2013).

Students should be included in the process: having learners at the table advances equity and engagement (Jankowski & Marshall, 2017). Additionally, maps can be shared with students during their educational journey. They will be able to internalize their goals and metacognitively to track their growth. They can actively participate and contribute to their own learning and development journey when maps are shared with them. They are engaged and invested in the learning and assessment process because they can see the destination their educators want them to reach and customize the pathway to get there for themselves. They can see the relevance of what they are asked to do to demonstrate progress and proficiency as they engage in formative and summative assessments for learning. They can offer feedback to make the maps-i.e., the curriculum, better serve them to assure their own success. When we explain the why of an assessment for a particular outcome or the why of content for any outcome and assessment to our student learners, it catalyzes distributive ownership and accountability of the educational endeavor. It makes everyone interested and engaged in learning, boosts learning efficacy, and makes the whole learning journey an invested, affirming enterprise for all those involved—faculty and students.

Students should be included in the process: having learners at the table advances equity and engagement (Jankowski & Marshall, 2017).

Maps can be shared with students during their educational journey. They will be able to internalize their goals and metacognitively to track their growth.

They can actively participate and contribute to their own learning and development journey when maps are shared with them. They are engaged and invested in the learning and assessment process because they can see the destination their educators want them to reach and customize the pathway to get there for themselves. They can see the relevance of what they are asked to do to demonstrate progress and proficiency as they engage in formative and summative assessments for learning. They can offer feedback to make the maps better serve them to assure their own success. When we explain the why of an assessment for a particular outcome or the why of content for any outcome and assessment to our student learners, it catalyzes distributive ownership and accountability of the educational endeavor. It makes everyone interested and engaged in learning, boosts learning efficacy, and makes the whole learning journey an invested, affirming enterprise for all those involved—faculty and students.

Mapping, including its creation and maintenance, is a continuous improvement exercise and must be a planned, periodic effort. It is not a one and done job but is rather an ongoing endeavor. While maps can be used in many ways, we will cover two crucial applications:

-

Review maps visually as stand-alone documents to uncover and address gaps in the curricula, scaffolding, or alignment.

-

Use the student performance assessment data that are connected to the mapped outcomes at the assessment and rubric levels to discover areas for improvement and change.

In the first type of review, one can review curricular maps to see if there are any learning levels (IDRMs) missing that need to be addressed so that students are set up to learn better with stronger and more thorough scaffolding. Conversely, one can see if the outcomes are overrepresented in the scaffolding (with too many hierarchical relationships) and remove those redundancies. Similarly, in assessment maps, one can systematically analyze a map and see if there are outcomes that are not being adequately assessed and, accordingly, make corrections to the curriculum and map to ensure that what is considered important for students to learn is being adequately assessed. Alternately, too many assessments focused on a select few outcomes is once again worth investigating and addressing to improve curricular efficacy.

In the second type of map review, when students are under performing on certain outcomes based on their assessment performance data, that information can be used to embark on and aid curricular and mapping reviews. This endeavor has the potential to reveal the underlying cause of the decline, such as misalignment in the curriculum or gaps in learning achievement. It allows educators to gain information about which students are underperforming on what outcomes and where to look to develop plans for success. This may include: introduction and reinforcement of outcomes at an earlier stages in the student journey, additional support in classrooms, or identification and support of vulnerable student groups who need better foundation, scaffolding, and/or instruction for success. This kind of trend analysis of assessment performance informs decisions for student learning interventions.

Thus, concrete assessment maps and performance review is central to continuous improvement because ongoing review and updating of maps help maintain the quality and rigor of the curriculum (Wang, 2015). Without action there is no continuous improvement or efficacy at any level.

The outlined strategies serve as catalysts for robust curriculum development, mapping, and ongoing reviews. They facilitate accurate decision-making for continuous improvement, enhancing the effectiveness of curricula, assessments, and educational practices. Well-structured maps and curricula, aligned with substantive assessments, are pivotal for the success of any educational initiative. They equip all stakeholders—faculty, students, and staff—with essential insights. Sharing or co-creating maps with students fosters empowering learning environments, enabling active and reflective participation in their own educational journey and assessment. This involvement provides students with a stronger sense of control in obtaining what they need from the program and curriculum.

When employed effectively, maps not only enhance engagement but also elevate the quality of curricula, aiding educators in achieving their educational objectives and making the teaching and learning experience more impactful. The use of maps in evaluating curricular efficacy, coupled with the potential insights they offer, proves to be a powerful tool. Successful and consistent mapping leads everyone toward the destination of achieving educational excellence and continuous improvement, fostering a journey of learning and success.

About the author

Dr. Divya Bheda is an education consultant with over 15 years of experience leading educator professional development in brick and mortar, and online learning contexts. She has led continuous improvement and DEI efforts at UT Austin, National University, and in the WSCUC region. Dr. Bheda is a leader in culturally relevant program evaluation, transformative outcomes assessment, and effective strategic planning for continuous improvement across all departments, disciplines, and divisions in higher education.

Her national and international workshops, panels, and keynotes focus on educational best practices to serve students. She imbues social justice in all she offers and champions equity and organizational responsiveness for student success. As a people developer and organizational capacity builder in the higher ed, non-profit, and ed tech spaces, she has facilitated, guided, and mentored many on the path to educational activism and meaningful change.

She holds a PhD in Critical and Socio-Cultural Studies in Education, an M.S. in Educational Leadership, and an M.A. in Mass Communication. Connect with Dr. Bheda on LinkedIn.

References

Al-Eyd, G., Achike, F., Agarwal, M., Atamna, H., Atapattu, D. N., Castro, L., Estrada, J., Ettarh, R., Hassan, S., Lakhan, S. E., Nausheen, F., Seki, T., Stegeman, M., Suskind, R., Velji, A., Yakub, M., & Tenore, A. (2018). Curriculum mapping as a tool to facilitate curriculum development: a new School of Medicine experience. BMC medical education, 18(1), 185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1289-9

Archambault, S.G. & Masunaga, J. (2015) Curriculum mapping as a strategic planning tool. Journal of Library Administration, 55(6), 503-519. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2015.1054770

Banta, T. W., & Palomba, C. A. (2015). Assessment essentials: Planning, implementing, and improving assessment in higher education (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Cuevas, U. M., Matveev, A. G., & Miller, K. O. (2010). Mapping general education outcomes in the major: Intentionality and transparency. Peer Review, 12(1), 10-15.

Eisner, E. (2002). The three curricula that all schools teach. in the educational imagination: on the design and evolution of school programs (3rd Ed.). Merrill Prentice Hall.

Hale, J. A. (2007). A guide to curriculum mapping: Planning, implementing, and sustaining the process. Corwin Press.

Harden, R. M. (2001). Guide No. 21: Curriculum mapping: A tool for transparent and authentic teaching and learning. Med Teach, 23, 123-137.

Hitchcock, C., Meyer, A., Rose, D., & Jackson, R. (2002). Providing new access to the general curriculum: Universal design for learning. Teaching exceptional children, 35(2), 8-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005990203500201

Jacobs, H. H. (2004). Getting Results with Curriculum Mapping. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD), 1703 North Beauregard Street, Alexandria, VA 22311. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED489051

Jacobs, H. H. (2010). Instructional cartography: How curriculum mapping has changed the role and perspective of the teacher. On excellence in teaching, 195-211.

Jacobs, H.H. (1997) Mapping the Big Picture: Integrating Curriculum and Assessment K–12 (Alexandria, VA, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED411323

Jankowski, N. A., & Marshall, D. W. (2017). Degrees that matter: Moving higher education to a learning systems paradigm. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing. https://www.learningoutcomesassessment.org/books/degrees-that-matter-moving-higher-education-to-a-learning-systems-paradigm/

Joyner (Melito), H.S. (2016), Curriculum Mapping: A Before-and-After Look at Faculty Perceptions of Their Courses and the Mapping Process. Journal of Food Science Education, 15: 63-69. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4329.12085

Joyner (Melito), H.S. (2016), Curriculum Mapping: A Method to Assess and Refine Undergraduate Degree Programs. Journal of Food Science Education, 15: 83-100. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4329.12086

Matveev, Alexei G.; Veltri, Natasha F.; Zapatero, Enrique G.; and Cuevas, Nuria M., "Curriculum Mapping: A Conceptual Framework and Practical Illustration" (2010). AMCIS 2010 Proceedings. Paper 515. http://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2010/515

Montenegro, Erick, and Natasha A Jankowski. “Equity and Assessment: Moving towards Culturally Responsive Assessment (Occasional Paper No. 29). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University.” National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA), 2017. https://ia800607.us.archive.org/17/items/ERIC_ED574461/ERIC_ED574461.pdf

National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment. (2018, December). Mapping learning: A toolkit. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University.

O'Rourke, J. A., Relf, B., Crawford, N., & Sharp, S. (2019). Are we all on course? A curriculum mapping comparison of three Australian university open-access enabling programs. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 59(1), 7-26. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1225528.pdf

Plaza, C.M., Draugalis, J.R., Slack, M.K., Skrepnek, G.H., & Sauer, K.A. (2007). Curriculum mapping in program assessment and evaluation. American journal of pharmaceutical education, 71(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj710220

Prideaux, D. (2003). ABC of learning and teaching in medicine. Curriculum design. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 326(7383), 268–270. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7383.268

Spencer, D., Riddle, M.D., & Knewstubb, B. (2012). Curriculum mapping to embed graduate capabilities. Higher Education Research & Development, 31, 217 - 231. http://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2011.554387

Stiehl, R. E., & Lewchuk, L. (2008). The outcomes primer : reconstructing the college curriculum (3rd ed.). Learning Organization.

Stiehl, R. E., Lewchuk, L. (2005). The mapping primer: Tools for reconstructing the college curriculum. United States: Learning Organization.

Sumsion, J., & Goodfellow, J. (2004). Identifying generic skills through curriculum mapping: a critical evaluation. Higher Education Research & Development, 23, 329 - 346. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436042000235436

Uchiyama, K., & Radin, J. (2009). Curriculum Mapping in Higher Education: A Vehicle for Collaboration. Innovative Higher Education, 33, 271-280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-008-9078-8

Udelhofen, S. (2005). Keys to curriculum mapping: Strategies and tools to make it work. Corwin Press. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483329079

Wang, C. (2015). Mapping or tracing? Rethinking curriculum mapping in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 40, 1550 - 1559. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.899343

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (1998). Understanding by design. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Winkelmes, M. (2013). Transparency in Teaching: Faculty Share Data and Improve Students' Learning. Liberal Education, 99. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:157833588